“People and collaboration over processes, methodologies, and tools.”

–The Threat Modeling Manifesto, Value #2

During our panel, my dear friend and longtime collaborator, Izar Tarandach, mentioned something that occurs so often when threat modelling as to be usual and customary. This happens so often, it is to be expected rather than being merely typical. We were speaking on Threat modelling for Agile software development practices at OWASP BeNeLux Days 2020. Izar was addressing the need for broad participation in a threat model analysis. As an example, he described the situation when an architect is drawing and explaining a system’s structure (architecture) at a whiteboard, and another participant at the analysis, perhaps even a relatively junior member of the team says, “but that’s not how we had to implement that part. It doesn’t work that way”.

I cannot count the number of times I’ve observed a disparity between what designers believe about system behaviour and how it actually runs. This happens nearly every time! I long since worked the necessity for uncovering discrepancies into my threat modelling methods. That this problem persists might come as a surprise, since Agile methods are meant to address this sort of disconnect directly? Nevertheless, these disconnect continue to bedevil us.

To be honest, I haven’t kept count of the number of projects that I’ve reviewed where an implementer as had to correct a designer. I have no scientific survey to offer. However, when I mention this in my talks and classes, when I speak with security architects (which I’m privileged to do regularly), to a person, we all have experienced this repeatedly, we expect it to occur.

In my understanding of Agile practice, and particularly SCRUM, with which I’m most familiar and practice, design is a team effort. Everyone involved should understand what is to be implemented, even if only a sub-team, or a single person actually codes and tests. What’s going on here?

I have not studied the cause and effect, so I’m merely guessing. I encourage others to comment and critique, please. Still, as projects get bigger with greater complexity, there are two behaviours that emerge from the increased complexity that might be responsible for disconnection between designers and implementers:

- In larger projects, there will be a need to offer structure to and coordinate between multiple teams. I believe that this is what Agile Epics address. Some amount of “design”, if you will (for want of a better word) takes place outside and usually before SCRUM teams start their cycles of sprints. This structuring is intended to foster pieces of the system to be delivered by individual, empowered Agile teams while still coming together properly once each team delivers. My friend Noopur Davis calls this a “skeleton architecture”. The idea is that there will be sufficient structure to have these bits work together, but not so much as to get in the way of a creative and innovative Agile process. That may be a rather tricky razor’s edge to achieve, which is something to consider as we build big, complex systems involving multiple parts. Nonetheless, creating a “skeleton architecture” likely causes some separation between design and implementation.

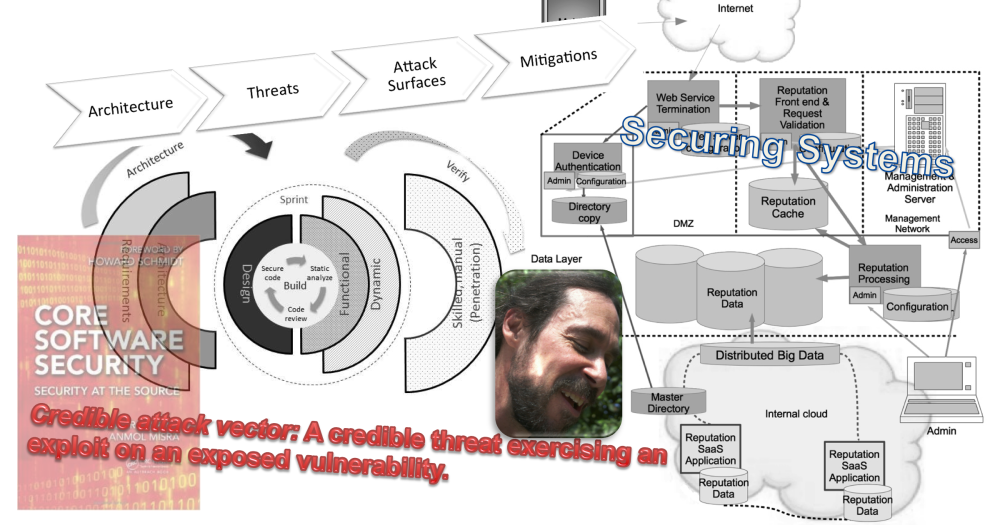

- As this pre-structuring becomes a distinct set of tasks (what we usually call architecture), it fosters, by its very nature, structuring specialists, i.e., “architects”. Now we have separation of roles, one of the very things that SCRUM was meant to bridge, and collapsing of which lies at the heart of DevOps philosophy. I’ve written quite a lot about what skills make an architect. Please take a look at Securing Systems, and Secrets Of A Cyber Security Architect for my views, my experiences, and my attempts to describe security architecture as a discipline. A natural and organic separation occurs between structurers and doers, between architects and implementers as each role coalesces.

Once structuring and implementing split into discrete roles, and I would add, disciplines, then the very nature of Agile empowerment to learn from implementing practically guarantees that implementations diverge from any plans. In the ideal world, these changes would be communicated as a feedback loop from implementation to design. But SCRUM does not specifically account for design divergences in its rituals. Designers need to be present during daily standup meetings, post-sprint retrospectives, and SCRUM planning rituals. Undoubtedly, this critical divergence feedback does occur in some organizations. But, as we see during threat modelling sessions, for whatever reasons, the communications fail, or all too often fail to lead to an appropriately updated design.

Interestingly, the threat model, if treated as a process and not a one-time product can provide precisely the right vehicle for coordination between doing and structure, between coding and architecture.

“A journey of understanding over a security or privacy snapshot.”

–The Threat Modeling Manifesto, Value #3

Dialog is key to establishing the common understandings that lead to value, while documents record those understandings, and enable measurement.

–The Threat Modeling Manifesto, Principle #4

When implementors must change structures (or protocols, or flows, anything that affects the system’s architecture), this must be reflected in the threat model, which must mirror everyone’s current understanding of the system’s state. That’s because any change to structure has the potential for shifting which threats apply, and the negative impacts from successful exploitations. Threat modelling, by its very nature, must always be holistic. For further detail on why this is so, I suggest any of the threat modelling books, all of which explain this. My own Secrets Of A Cyber Security Architect devoted several sections specifically to the requirement for holism.

Thus, a threat model that is continually updated can become the vehicle and repository for a design-implementation feedback loop.

Value #5:

“Continuous refinement over a single delivery.”

Threat model must, by its very nature deal in both structure (architecture) and details of implementation: engineering. Threat modelling today remains, as I’ve stated many times, both art and science. One imagines threats as they might proceed through a system – often times, a system that is yet to be built, or is currently in the process of building. So, we may have to imagine the system, as well.

The threats are science: they operate in particular ways against particular technologies and implementations. That’s hard engineering. Most defenses also are science: they do what they do. No defense is security “magic”. They are all limited.

Threat modelling is an analysis that applies the science of threats and defenses to abstracted imaginings of system through mental activity, i.e., “analysis”.

Even though a particular weakness may not be present today, or we simply don’t know yet whether it’s present, we think through how attackers would exploit it if it did exist. On the weakness side, we consider every potential weakness that has some likelihood of appearing in the system under analysis, based upon weaknesses of that sort that have appeared at some observable frequency in similar technologies and architectures. This is a conjunction of the art of imagining coupled to the science of past exploitation data, such as we can gather. Art and science.

The Threat Modeling Manifesto’s definition attempts to express this:

“Threat modeling is analyzing representations of a system to highlight concerns about security and privacy characteristics.”

Threat modelling then requires “representations”, that is, imaginings of aspects of the target of the analysis, typically, drawings and other artifacts. We “analyze”, which is to say, the art and science that I briefly described above for “characteristics”, another somewhat imprecise concept.

In order to be successful, we need experts in the structure of the system, its implementation, the system’s verification, experts in the relevant threats and defenses, and probably representatives who can speak to system stakeholder’s needs and expectations. It often helps to also include those people who are charged with driving and coordinating delivery efforts. In other words, one has to have all the art and all the science present in order to do a reasonably decent job. To misquote terribly, “It takes a village to threat model”[1].

Participation and collaboration are encapsulated in the Threat Modeling Manifesto.

Consider the suggested Threat Modeling Manifesto Pattern, “Varied Viewpoints”:

“Assemble a diverse team with appropriate subject matter experts and cross-functional collaboration.”

And, our Anti-pattern, “Hero Threat Modeler” speaks to a need to avoid over-dependence on a single individual:

“Threat modeling does not depend on one’s innate ability or unique mindset; everyone can and should do it.”

Another frequent occurrence during threat modelling sessions will be when a member of the team who would not have normally been included during leader-only threat modelling names a weakness of which the leaders were unaware, or which other active participants simply missed in their analysis. Diversity in threat modelling applies more system knowledge and understanding, which leads to more complete models.

Since attackers are adaptive and creative and there are a multiplicity of objectives for attack, diversity while modelling counters attacker variety. I will note that through the many threat models I’ve built (probably 1000’s), I’ve been forced to recognize my limitations, that I am perfectly capable of missing something obvious. It’s my co-modelers who keep me honest and who check my work.

Failure to uncover the differences between representation and implementation risk failure of one’s threat model. As Izar explained, even a lead designer may very likely not understand how the system actually works. To counter this problem, both Izar and I, and probably all the co-authors of the Threat Modeling Manifesto account for these misunderstandings through our threat modelling processes. One way is to ensure that a diverse and knowledge collection of people participate. Another is to begin a session by correcting the current representations of the system through the collected knowledge of participants.

I often say that one of the outcomes of broad threat model participation has nothing to do with the threat model. Attendees come away with a fuller understanding of how the system actually works. The threat model becomes a valued communication mechanism with effects beyond its security and privacy purposes. As both art and science, we find it critical to be inclusive rather than exclusive when threat modelling. Your analyses will improve dramatically.

Cheers,

/brook

[1] Please don’t make assumptions about my personal politics just because I mangled the title of one of Hilary Clinton’s books. Thanks