Ah, sigh, Marcus and I almost never agree! And, this often a matter of lexicon and scoping. In this case, Marcus stays away from the thorny issue of risk methodology. But this, I think, is precisely the point to discuss.

Think about the word “risk”. How many definitions have you seen? The word is so overloaded and imprecise (and undefined in Marus’ Rant) that saying “risk” without definition will almost surely undermine the technical/C-level management dialog!

I would argue that the reasons for failure of the security to executive risk dialog have less to do with C-level inability to grasp security issues than it has to do with our imprecision in describing risk for them!

Take Jack Jones. When at Nationwide, he found himself mired within Ranum’s rant. I’ve been there, too. Who hasn’t?

To solve the problem and feel more effective, he spent 5 years designing a usable, repeatable, standardized risk methodology. (FAIR. And yes, you’ve heard me rant about it before)

Jack described to me just how dramatically his C-level conversations changed. Suddenly, crisp interactions were taking place. What changed?

I see the failure of the dialog has having these components:

- poor risk methodology

- poor communication about risk

- not treating executives as executives

Let me explain.

Poor risk methodology is the leading cause of inaccurate and unproductive risk dialog. When we say “risk” what is our agreed upon meaning?

I’ve participated in many discussions that treat risk as equivalent with an open vulnerability. Period.

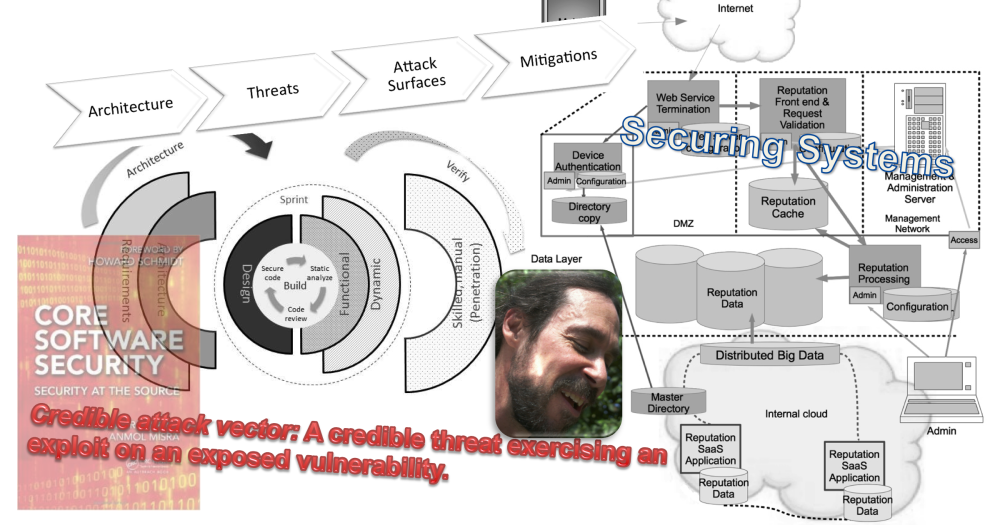

But, of course, that’s wrong, and actually highly misleading. Is “risk” a vulnerability added to some force that has motivation to exercise the vulnerability (“threat” – I prefer “threat agent” for this, by the way)? That again is incomplete – but that is often what we mean when we say information security risk. And, again, it’s wrong.

In fact, as I understand it, threat can be conceived as the interaction between the components that create a credible threat agent who has sufficient motivation and access in order to exercise an exposed vulnerability. This is quite complex. And, unfortunately, the mathematics involved may be beyond many security practitioners?> Certainly, when in the field these mathematics may be too much?

Most of us security professionals are pretty good on the vulnerability side. We’re good at assessing whether a vulnerability is serious or not, whether its impact can be far-reaching or localized, how much is exposed. It seems to me, that it’s the threat calculation that’s the difficult piece. I’ve seen so many “methodologies” that don’t go deep enough about threat. Certainly there are reasonable lists of threat agent categories. And, maybe the methodology includes threat motivation. Maybe they include capability? But motivation, capability, risk appetite, access? Very few. And how do you calculate these?

And then there’s the issue of impact. In my practice, I like to get the people close enough to business to assess impact. That doesn’t mean I don’t have a part in the calculation. Often times the security person has a better understanding of the potential scope of vulnerability and the threats that may exercise it than a business person. Still, a business person understands what the loss of their data will mean. However impact is assessed, it has a relationship to the threat and vulnerability side. Together these are the components of risk.

I think in this space, it probably doesn’t make sense to go into the various calculations that might go into actually coming up with a risk calculation? Indeed, this is a nontrivial matter, though I have made the case that any consistent number between zero and one on threat and vulnerability side of the equation can effectively work. (But that’s another post about the hour at an RSA conference presentation that helped me to understand this little bit of risk calculation trickery.)

In any event, hopefully you can see that expressing some reasonable indication of risk is a nontrivial exercise?

Simply telling an executive that there is a serious vulnerability, or that there’s a flaw in an architecture that “might” lead to serious harm waters down the risk conversation. When we do this, we set ourselves up for failure. We are likely to get “I except the risk”, or, an argument about how serious the risk is. Neither of these is what we want.

And this is why I mention “poor communication of risk” as an important factor in the failure of risk conversations. Part of this is our risk methodology, as I’ve written. In addition, there is the clarity of communication. We want to keep the conversation focused on business risk. We do not want to bog down in the rightness or wrongness of a particular project or approach, or an argument about the risk calculation. (And these are what Ranum describes) In my opinion, each of these must be avoided in order to get the dialog that is needed. We need a conversation about the acceptable business risks for the organization.

Which brings me to “treating executives as executives”. When we ask executives to come down into the weeds and help us make technical decisions we are not only inviting trouble, but we are also depriving ourselves and the organization of the vision, strategy, and scope that lays at the executive level. And that’s a loss for everyone involved.

I think we make a big mistake asking the executive to assess our risk calculation. We should have solid methodologies. It must be understood that the risk picture were giving is the best possible given information at hand. There needs to be respect from executive to information security that the risk calculations are valid (as much as we can make them).

No FUD! Don’t ask your executives to decide minor technical details. Don’t ask your executives to dispute risk calculations. Instead, ask them to make major risk decisions, major strategic decisions for your organization. Treat them as your executives. Speak to them in business language, about business risks, which include your assessment about how the technical issues will impact the organization in business terms.

I’ve been surprised at how my own shift with respect to these issues has changed my conversation away from pointless arguments to productive decision-making. And yes, Marcus, amazingly enough, bad projects do get killed when I’ve expressed risk clearly and in business terms.

Sometimes it makes business sense to take calculated risks. One of the biggest changes I’ve had to make as a security professional is to avoid prejudice about risk in my arguments. Like many security folk, I have a bias that all risk should be removed. When I started to shift to that, I started to get more real dialog. Not before.

So, Marcus, we disagree once again. But we disagree more about focus rather than on substance? I like to focus on the things that I can change, rather than repeating the loops of the past endlessly.

Cheers,

Brook