November 13th, 2013, I spoke at the annual BSIMM community get together in Reston, Virginia, USA. I had been asked to co-present on Architecture Risk Assessment (ARA) and threat modeling along side Jim Delgrosso, long time Cigital threat modeler. We gave two talks:

- Introduction to Architecture Risk Assessment And Threat Modeling

- Scaling Architecture Risk Assessment And Threat Modeling To An Enterprise

Thanks much, BSIMM folk, for letting me share the tidbits that I’ve managed to pick up along my way. I hope that we delivered on some of the promises of our talks? One of my personal values from my participation in the conference was interacting with other experienced practitioners.

Make no mistake! ARA-threat modeling is and will remain an art. There is science involved, of course. But people who can do this well learn through experience and the inevitable mistakes and misses. It is a truism that it takes a fair amount of background knowledge (not easily gained):

- Threat agents

- Attack methods and goals used by each threat agent type

- Local systems and infrastructure into which a system under analysis will go

- Some form of fairly sophisticated risk rating methodology.

These specific knowledge sets sit on top of significant design ability and experience. The assessor has to be able to understand a system architecture and then to decompose it to an appropriate level.

The knowledge domains listed above are pre-requisite to an actual assessment. That is, there are usually years of experience in system and/or software design, in computer architectures, in attack patterns, threat agents, security controls, etc., that the assessor brings to an ARA. One way of thinking about it is that ARA/threat modeling is applied computer security, computer security applied to the system under analysis.

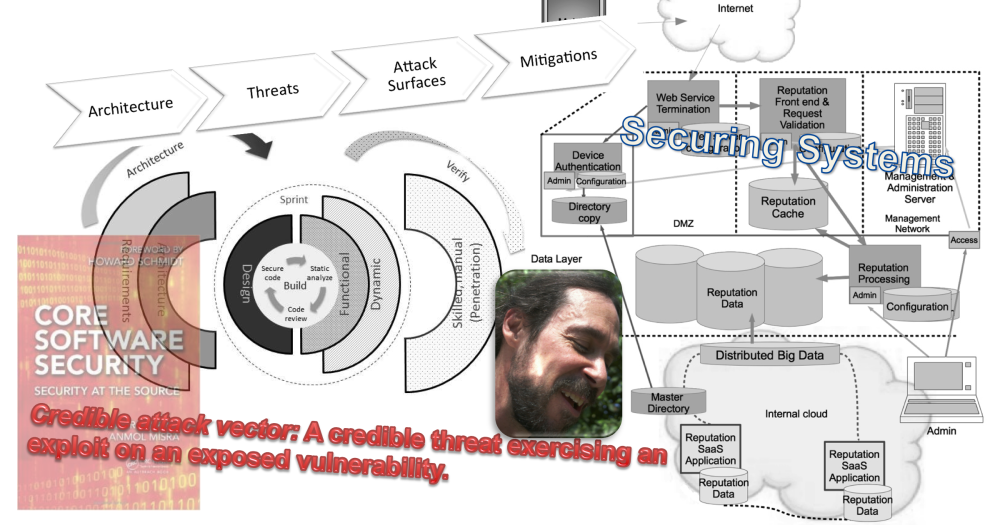

Because ARA is a learned skill with many local variations, I find it fascinating to match my practice to practices that have been developed independent of mine. What is the same? Where do we have consensus? And, importantly, what’s different? What have I missed? How can I improve my practice based upon others’? These co-presentations and conversations are priceless. Interestingly, Jim and I agreed about the basic process we employ:

- Understand the system architecture, especially the logical/functional representation

- Uncover intended risk posture of the system and the risk tolerance of the organization

- Understand the system’s communication flows, to the protocol interaction level

- Get the data sensitivity of each flow and for each storage. Highest sensitivity rules any resulting security needs

- Enumerate attack surfaces

- Apply relevant active threat agents and their methodologies to attack surfaces

- Filter out protected, insignificant, or unlikely attack vectors and scenarios

- Output the security that the system or the proposed architecture and design are missing in order to fulfill the intended security posture

There doesn’t seem to be much disagreement on what we do. That’s good. It means that this practice is coalescing.The places were we disagree or approach the problem differently I think are pretty interesting.

Gary McGraw calls security architecture misses, “flaws”. Flaws as opposed to software bugs. bugs can be described as errors in implementation, usually, coding. Flaws would then be those security items which didn’t get considered during architecture and design, or which were not designed correctly (like poorly implemented authentication, authorization, or encryption). I would agree that implementing some sort of no entropy scramble and then believing that you’ve built “encryption” is, indeed both a design flaw and an implementation error*.

I respect Gary’s opinion greatly. So I carefully considered his argument. My personal “hit”, not really an opinion so much as a possible rationale, is that “flaw” gets more attention than say, “requirement”? This may especially be true at the senior management level? Gary, feel free to comment…

Why do I prefer the term “requirement”? Because I’m typically attempting to fit security into an existing architecture practice. Architecture takes “requirements” and turns these into architecture “views” that will fulfill the requirements. So naturally, if I want security to get implemented, I will have to deliver requirements into that process.

Further, if I name security items that the other architects may have missed, as “flaws”, I’m not likely to make any friends amongst my peers, the other architects working on a system. They may take umbrage in my describing their work as flawed? They bring me into analysis in order to get a security view on the system, to uncover through my expertise security requirements that they don’t have the expertise to discover.

In other words, I have very good reasons, just as Gary does, for using the language of my peers so that my security work fits as seamlessly as possible into an existing architecture practice.

The same goes for architecture diagram preferences. Jim Delgrosso likes to proffer a diagram template for use. That’s a great idea! I could do more with this, absolutely.

But once again, I’m faced with an integration problem. If my peers prefer Data Flow Diagrams (DFD), then I’d better be able to analyze a system based upon its DFD. If architects use UML, I’d better be able to understand UML. Ultimately, if I prize integration, unless there’s no existing architecture approach with which to work, my best integration strategy is to make use of whatever is typical and normal, whatever is expected. Otherwise, if I demand that my peers use my diagram, they may see me as obstructive, not collaborative. I have (so far) focused on integration with existing practices and teams.

As I spend more time teaching (and writing a book about ARA), I’m finding that having accepted whatever I’ve been given in an effort to integrate well, I haven’t created a definitive system ARA diagram template from which to work (though I have lots of samples). That may be a miss on my part? (architectural miss?)

Some of the different practices I encountered may be due to differing organizational roles? Gary and Jim are hired as consultants. Because they are hired experts, perhaps they can prescribe more? Or, indeed, customers expect a prescriptive, “do it this way” approach? Since I’ve only consulted sparingly and have mostly been hired to seed and mentor security architecture practices from the inside, perhaps I don’t have enough experience to understand consultative demands and expectations? I do know that I’ve had far more success through integration than through prescription. Maybe that’s just my style?

You, my readers, can, of course, choose whatever works for you, depending upon role, maturity of your organization, and such.

Thanks for the ideas, Jim (and Gary). It was truly a great experience to kick practices around with you two.

cheers,

/brook

*We should be long past the point where anyone believes that a proprietary scramble protects much. (Except, of course, I occasionally do come across exactly this!).